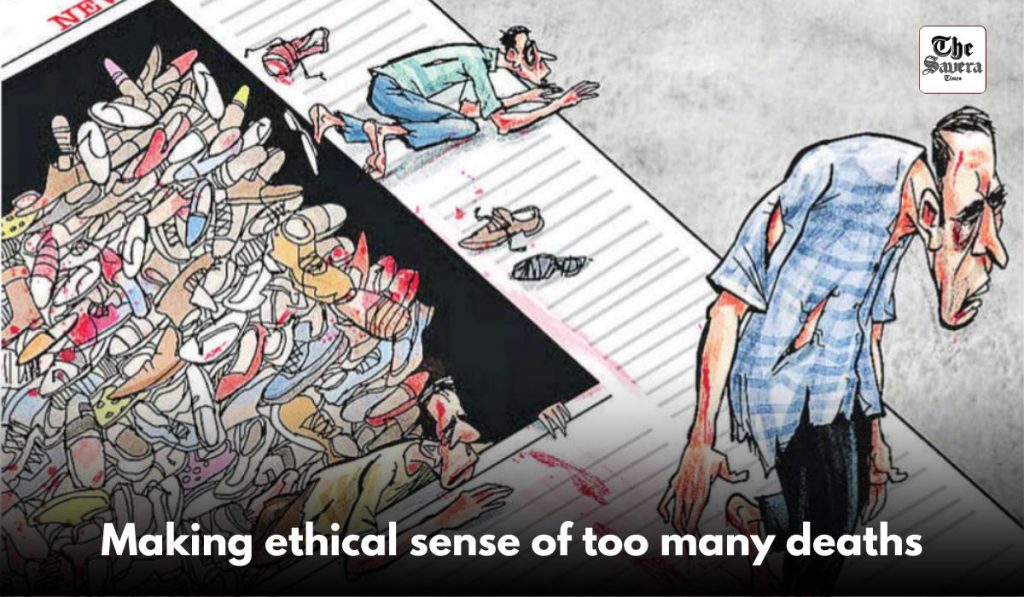

Over the past month, newspapers have been packed with reports of death. Death, in effect, haunts the newspaper. And the individual reading about it feels a sense of futility and helplessness.

The citizen— as a reader, spectator or critic—feels the importance of ethicality. He realises a mere act of fury will not be enough; one has to rework one’s concepts and move towards action. While discussing this, a philosopher friend of mine made an important distinction. He distinguished between individual death and collective death.

Individual death, in search of structure and meaning, has found its symbolism and its philosophers. It fits into the philosophy of everydayness and the concept of rite of passage. It fits into the cosmos. Collective death, on the other hand, offers no such possibility. It is in this context that we shall analyse five recent events—the Iran-Israel war, the question over the Gaza Strip, the Pahalgam incident, the Air India accident and the stampede in Bengaluru.

Haunting the first two events stands the figure of Donald Trump, the American president, seen as a clown, a jester, a monster. He is always a caricature. Despite all the attention given to him, Trump has not acquired a full semiotic effect. Symbolically, he represents a new wave—he has not only created a new politics beyond the Cold War, but he has also provided it with a new sociology of death.

Trump has become the master of collective death while playing the deceitful role of a peacenik. He pretended to arbitrate between Iran and Israel while getting ready to bomb Iranian installations. There is a sense of machismo—a technological superiority— about Trump. He feels he and Israel are mature enough to be the masters of nuclear death.

Iran and most of the Third World are immature for nuclear development. Trump in a master of triage. He talks about the dispensability and erasure of the Third World. For him, most of Palestine is real estate to be redeemed from the indigenous people. He feels the migrant is a disposable creature and Mexican migrants, in particular, are utterly dispensable.

He treats Gaza as a piece of real estate. Indigenous people, refugees, migrants and marginals—all belong in the dustbin of collective death. Benjamin Netanyahu is a successful mimic of Trump. He believes that Israel should have superiority over others in the region. Israel’s hypocrisy becomes obvious in the way it has made Palestine into a laboratory of real estate and military operations.

It is ironic that Israel, a product of the Holocaust, should have little sense of its own genocidal propensities. Its attempts to starve the people of Palestine— because they are seen as irrelevant—is a sheer act of social triage. Children’s drawings capture this beautifully. America as a nation is usually symbolised by the Statue of Liberty— standing for generosity and openness to migrants and marginal dissenters from other countries.

Children’s drawings show Trump demolishing the statue and installing himself. Trump is the Frankenstein of a new politics. He has no sense of nuclear war. The American bombing of Iran is an obscenity in that sense. It turned death into a casual fact by advertising the number of casualties. Death is like an advertisement—a testimony of America and Israel.

One of the ironies lies in the fact that the one of the most outstanding essays capturing the philosophy of the other was written by Martin Buber, the Israeli philosopher. He made a classic distinction between ‘I-thou’ (relationship characterised by authentic, direct encounters where the other is seen as a whole person) and ‘I-it’ (treating the other as an object, a means to an end).

Buber, like Ivan Illich, argues that philosophy is born with a new grammar of the other. Barbarism becomes permissible when Ithou becomes I-it. Necrophilia as barbarism is genocidal and it’s the Western powers that are the most genocidal. Collective death, thus, becomes an everyday possibility in international relations.

This tendency is also seen in the Pahalgam incident. Its prelude is a speech by General Asim Munir that death and genocide can be legitimised through difference. The Hindu is different from the Muslim and should, therefore, should be eliminated. The terrorists in Pahalgam asked the tourists a single question: whether they were Muslims, and the nonMuslims got shot after that. Death in Pahalgam was minimal next to the Israeli air strikes.

Both were fascinating in terms of the numbers. Terror, like the air strikes, has a statistical role that eliminates storytelling. Even in Pahalgam, most casualties were reduced to stark anonymity. The life stories get lost in the paradigm of lifelessness. One also sees the inanity of the philosophy of death. It is enough to kill if you are ‘different’. In contrast, for Buber, the differences are what create humanity and a philosophy of humanity.

Collective death threatens the world as a civilisation. That’s why international relations today are impoverished in the philosophical and ethical senses. The Air India accident and stampede over cricket celebrations in Bengaluru bring out the bureaucratic prelude to death. Both events were marked by a benign neglect of civic action.

One has to ask the question whether airports should be constructed in densely populated neighbourhoods. Real estate operations and bureaucratic red tape eventually set the scenario of dramatic deaths. One rarely connects the bureaucratic file to the air accident or the cricket stampede. What is stark about both events is that they remained scandals for a week and then were forgotten. Erasure and forgetfulness mark reportage in the information age.

Death— especially, collective death—is forgotten as yesterday’s newspaper. Whatever its presence, collective death shows the emptiness of ethics. Today, collective death is industrialised in its production and consumption. Even when it evades memories, it haunts the basis of our civilisation.

Trump is not the beginning of a new age, but the symbol of a dying one. America needs to rethink itself as a civilisation because its indifference to death marks it as a genocidal country.

The transition from a democracy to being genocidal is an ironic one. It is in this context that India needs to invent a new ethical politics. Today, ethics compose necrophile regimes. And their technicalities and passivity are passed off as diplomacy.

-(Views are personal)